Higher relevance (and more effort) with Preference Centers

If you only send each recipient emails that really interest them, you should achieve significantly better results and happier customers — that's the concept behind preference centers. The benefits of more targeted communication are obvious:

- Higher relevance and acceptance by recipients

- Less inactivity and fewer cancellations

- Better KPIs for marketing

- Better deliverability

Of course, email marketing managers can also tailor their newsletter emails to the respective recipient without a preference center by analyzing their purchases, clicks and website behavior — assuming recipient consent to tracking — and addressing their target groups accordingly with personalized offers. However, evaluating this data and managing individual communication requires a certain amount of machine intelligence and manual design and work. For many CRM marketing planners, it seems obvious to let subscribers decide for themselves which content they are interested in and even how often they want to receive emails about it.

Where are "manage profile" pages suitable?

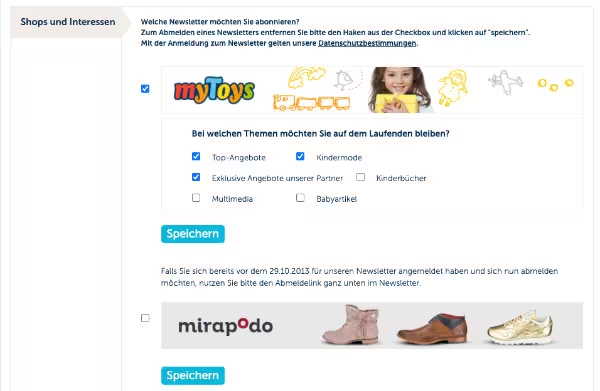

On a landing page for profile and interest management, each recipient can define their personal preferences with regard to subscribable topics or email formats (more or less) in detail: Do I just want news about bicycles or also about other outdoor sports? Do I just want to be notified of special offers but not receive fashion news?

Senders offer interest management features at various points in the customer life cycle. This type of interest inquiry is the most popular when registering or as part of the welcome route. The idea: At the time of registration, interest in the content offered is greatest and so is the willingness to take a few minutes to “fine-tune”.

“Wizards”, which guide subscribers step by step through clear profiling questions, have the best success rates. A clear benefit argument is very useful: What is the added value for the recipient to provide certain information? This increases customer trust (“We need your zip code to show you nearby events and offers.”) and provides additional incentives (“Looking for a birthday gift? Then tell us your date of birth”). Both lower the inhibition threshold for disclosing personal data.

How current are the interests in the Preference Center?

In addition or as an alternative to the subscription start query, many companies with profile management offer their email subscribers and customers the opportunity to refine their interest information at any time. This is usually hidden in the footer area of the email (“Change email preferences”, “Manage profile”).

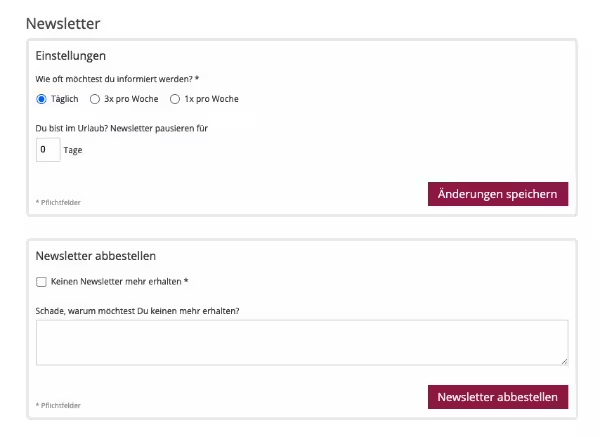

Experience has shown, however, that such preference centers are only actively used and maintained by very few email recipients. We see an exception to this rule among companies whose standard email delivery frequency is very high: If customers want to continue to receive their emails, but not in full, the Preference Center is used to channel the volume of emails. However, this too usually happens once and then never again — even though interest in other, new product categories or offers has now increased.

This reveals a general problem with preference centers: The information on interests and preferences quickly becomes outdated and does not reflect the full reality.

As a result of this support, companies that incentivize the maintenance of the recipient profile have a high profiling rate once in the customer lifecycle: The entrainment effect leads to an adjustment, but the information then remains that way until you unsubscribe.

A customer is often confronted with the Preference Center only after clicking on the unsubscribe link: In order to avert the imminent loss of the recipient, the unsubscribe landing page offers to individually adjust the content and frequencies instead of a complete opt-out.

Commit promises

One challenge with email profile management that should not be underestimated is that the recipient expects the promise of tailor-made information to be fulfilled. Has the customer explicitly stated that they are only interested in Asian cuisine, does a corresponding recipe have to be included in every newsletter in order to fulfill the promise? And if certain content is not desired, the advertiser must be technically able to remove this content from his emails (using modular emails) and offer sufficient alternative content. The same applies to frequency: Can the recipient limit the maximum number of emails using frequency control (“frequency capping”), must all emails be prioritized internally: Which email has priority? Newsletter before final sale, personal product recommendations before anniversary email? This quickly becomes complicated, especially with automated routes.

That means:

- Complex preference management is conceptually and technically complex.

- Email routes, frequencies and content must be served accordingly.

When introducing interest management, a realistic cost-benefit assessment of expenses is therefore important. From a technical point of view, it must be clarified whether the necessary infrastructure is available to establish preference and frequency management with all exclusion criteria.

Who has control over marketing content and frequencies?

As a rule, preference management should not be designed in such a way that the selection of interests takes the form of separate advertising consents for different types of newsletters. For example, if a recipient subscribes to the monthly event newsletter offered in profile management, the advertiser cannot flexibly send him a promotional email about seminar places that have become vacant at short notice — as this would have to be sent outside of the newsletter's monthly rhythm. To ensure that push marketing does not limit its ability to communicate content flexibly in different email formats, in a specific example, it would simply have been necessary to offer “events” instead of “event newsletters.” By the way, it is just as problematic to request consent in accordance with internal divisional structuring instead of taking the customer's point of view.

Our recommendation: Frequency and topic control should not be completely left to the customer. In the best case, expressions of interest are taken for what they are: interests. For example, it is possible to ask which topics are particularly important to a customer.

And even then, these interests only show what the customer is currently engaged in. A customer who is only interested in women's clothing at time X may no longer adjust this information in the Preference Center — even if she would have developed an interest in DIY, children's clothing or products from other product ranges in the meantime. This is also a problem when it comes to product range expansions and new products, as interest in them could not be interrogated in the past.

An opt-in should therefore be as broad as possible. Interests and website behavior can be used as a combination to make the content as relevant as possible for the user.

As described, however, the first question should be whether such a differentiation of one's own communication offerings makes sense and is technically feasible at all. Alternatively, it is always possible to design separate newsletters for product segments with completely separate target groups and no cross-selling potential. For companies with a very large product portfolio, preference centers can be a good way to establish highly relevant communication with their recipient groups despite their breadth. In any case, preference centers mean work — but when used correctly, they are rewarded by the benefits mentioned above!